- Art Project Google Museum Exhibits

- Google Arts And Culture Website

- Art Google Programs

- Google Art Project Prado Museum

The rules are quite simple: pick your favorite art, find three things lying around your house, and use them to recreate the artwork. The museum shared some of the best creations, and people were. Imagine being able to see artwork in the greatest museums around the world without leaving your chair. Driven by his passion for art, Amit Sood tells the story of how he developed Art Project to let people do just that.

Warning: Use of undefined constant user_level - assumed 'user_level' (this will throw an Error in a future version of PHP) in /home/commons/public_html/wp-content/plugins/ultimate-google-analytics/ultimate_ga.php on line 524Google Art Project

Google Art Project: a dizzying accumulation of artworks, reproduced with the kind of precision, high contrast and impeccable resolution capable of thrilling the technophile and a tech-skeptic alike. Every time I visit the site, I find a new favorite work, one that is particularly marvelous when I have zoomed as deep as I can. Today, I am made breathless by a corner of the work, Virgin and Child, from 1520, by Lucas Cranach the Elder. This is a corner I would likely never have noticed if I were looking at the real painting hanging in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. I have zoomed in not on the faces of the Virgin and Child, but on a background detail, the tendrils of the grape vine that twist and curl off the end of a trellis behind the figures. In this zoom, the trellis, obviously prefiguring the cross, is a meticulous buildup of wavering brown and grey lines. The edges of each gray-green grape leaf are jagged and sharp like knives. I can clearly picture a tiny paintbrush in Cranach's hand and the way his arm muscles must have tensed to paint each stroke with that kind of precision. But in truth, what I love the most about this zoomed-in view, is how well I can see the cracks, worn over nearly five centuries, that turn this oil-on-wood panel into a mosaic of tiny pieces. Critics discussing the Google Art Project have argued that while the Project shows artworks with great detail, it disconnects us from the their 'aura.'[1] I am not sure what defines 'aura'[2] for these critics, but to me, the way Google Art Project allows us to see the marks of time on the surface of the Cranach painting, better than we could in front of the painting live, imbues it with another kind of aura, an aura that supports and furthers our already-established reverence for art.

On the Zoomed-in detail of Lucas Cranach 'Virgin and Child,' the cracks of age are visible

In Contrast, here is the reproduction of 'Virgin and Child' as it appears on the Pushkin Museum Website

Art Project Google Museum Exhibits

As explained by Bolter and Grusin, digital interfaces like Google Art Project, progress along two conflicting logics: the logic of hypermediacy, and the logic of transparent immediacy. According to the logic of transparent immediacy, the medium that is most effective is the one that erases itself. According to the logic of hypermediacy, in contrast, what is valued and admired is the multimedia interface, an interface that is a fragmented, heterogeneous collage of links and functions. We both want to look at a medium, and for this hypermediacy is the most effective, and through a medium, unimpeded, at its content, and for this transparent immediacy is the best logic.[3] Furthermore, remediation is the defining characteristic of digital new media. New media is 'the representation of one medium in another.'[4] If, as Bolter and Grusin argue, the competing logics of immediacy and hypermediacy, in addition to the trait of remediation are the defining characteristics of digital new media, than Google Art Project is its poster child. Google Art Project is a highly layered remediation, representing museums representing art works, a medium representing a medium. It is also both hypermediated –with dozens of possible links to click on each page, and obsessed with achieving immediacy –both the 'museum view' and the incredible zoom capabilities of Google Art Project attest to this.

Google Art Project was launched in January 2011, in cooperation with 17 museums in the United States and Europe. Today, it partners with over 230 museums from 40 countries around the world, and features over 30,000 artworks.[5] More museums are signing on every day. With the kind of user-friendly interface we have come to expect from Google, a visitor can browse for hours, scrolling through the artwork by institution, by artist, or even by user-generated galleries. In sum, the Google Art Project is becoming an important player in the Artworld, and one that it is high time for scholars to assess critically. This is the task I take on in this essay. Three central questions frame my thinking. First, how does meaning-making work on Google Art Project? More specifically, how much is this meaning-making a continuation of the ways we have already been trained through Artworld institutions to understand art, and how much doe Google Art Project bring new variables into the system? In particular, does Google Art Project mediate symbolic capital in a way that promotes or devalues the museum function? In answer to these questions I argue that Google Art Project does not, and cannot revolutionize the way we understand art. No single new technology can have that much influence on a well established social system. While technology has a role to play in cultural change, social functions are far more important divers of cultural configurations. Observing the content of the site as it is today, it is clear that Google Art Project does not break down as much as continue to promote the hierarchies and cultural capital that have long been upheld by the Artworld.

Nonetheless, Google Art Project does show some potential to shift the Artworld functions in small ways. The Project, undoubtedly part of the Artworld, is also a node in two other networks: the Google brand name network, and the web/cultural interface network. In its position at the center of these interlinking networks, Google Art Project runs into conflicting purposes. In particular, the Web/cultural interface network functions as a general equalizer, which contradicts the hierarchy-building function of the Artworld. It is in negotiating these frictional functions, that Google Art Project breaks away a tiny bit from the limits of the Artword to create a space of meaning-making slightly different from other, older, Artworld spaces.Already, I have stumbled upon a half dozen examples of art works and art institutions included in the project that destabilize, rather than enforce a rigid high-art distinction. Furthermore, the project is still in its infancy. As I have observed it over the course of even a few months, the trend in its development is undeniably a development towards a more democratic, more inclusive, and broader, definition of art.

In attempting to articulate how art and museums have functioned before Google Art Project, I borrow the ideas of a number of different philosophers, cultural theorists, and media scholars. In particular, the writing of Pierre Bourdieu, and his ideas about symbolic capital are informative in understanding the Artworld and Google Art Project's developing role.

Creating Value in the Artworld: Bourdieu's Theory of Symbolic Capital

The purpose of 'the Artworld,' is to maintain the cultural category of art.[6] This idea was articulated early by Arthur Danto, and later developed further by Bourdieu. This insight recognizes that what makes something art is not an inherent property in the art object, but is determined and reinforced by a complex social process. Institutions like schools, museums, art galleries, and art auction houses, as well as roles like curators, art historians, and art collectors are all part of the Artworld, and play their (often invisible and/or unconscious) parts in the process of maintaining the cultural category of art. The museum's function is to confer prestige, authority, memory, validation and a cumulative art historical narrative on the works of high art. In this way, a museum is less a container for artifacts, and more a mediator of the museum function. Since it was founded in 2011, and more and more as it expands its reach, Google Art Project is another player in this game, largely following the rules of the museum function.

As Bourdieu explains, the Artworld runs on an economy of cultural capital. Capital means more than just money, in fact, the mercantile exchange of money for goods is just one case among many kinds of exchange of capital. This is central to Bourdieu's concept, because 'it is impossible to account for the structure and functioning of the social world unless one reintroduces capital in all its forms and not solely in the one form recognized by economic theory.'[7] So if capital is more than just money, what is it? For Bourdieu, capital comes in three basic guises: economic capital (the most easily convertible to money), social capital (largely reducible to social connections) and cultural capital.[8] Cultural capital itself can take one of three forms: Embodied, objectified, institutionalized. These three forms are to be found, respectively in people, in cultural objects and technologies, and in broader social institutions. All three of these play a role in the economy of the Artworld. Embodied capital requires personal investment and is nearly impossible to transfer from one person to another. This is the kind of capital art historians build up when they put in hours into studying and writing about art. Institutionalized capital, on the other hand, is codified in a complex system. It is 'sanctioned by legally guaranteed qualifications, formally independent of the person of their bearer.'[9] Bourdieu's central example of institutional capital is the university degree, however any socially sanctioned institutions –including museums – can bestow institutional capital on an object or person, 'as if by collective magic,'[10] instantly making the consecrated object or person more valuable. Embodied cultural capital has to constantly work to prove itself, and can be lost with injury to the bearer. Institutional cultural capital, once achieved, is far more stable.

There are two important aspects that make Bourdieu's insights into capital so profound. First, all the types of capital are fungible –they all can be converted into monetary gains in the long run. Second, and particularly relevant to the functioning of the Artworld, cultural capital is routinely disavowed and misrecognized. The Artworld functions by pretending not to be about capital, when in fact, nearly everything it does is done for the purpose of long term profit. Bourdieu insists that we understand how 'economic capital is at the root of all the other types of capital… and these transformed, disguised forms of economic capital, never entirely reproducible to that definition, produce their most specific effects only to the extent that they conceal (not least from their possessors) the fact that economic capital is at their root.'[11] Participants in the Artworld, and members of society outside of it, collectively misrecognize where value comes from in the Artworld, as well as the central importance of capital in the museum function. This misrecognized capital, Bourdieu terms 'symbolic capital.'[12] Common wisdom holds that the value of a work of art comes from something in the creative act of the artist. In fact, it is the museum professional or art businessperson who 'consecrates' the work and gives it its value. The museum professional however, has to believe, or at least pretend, that the value comes from properties of the artwork itself, because that is the logic of symbolic capital. Now the question is where does the museum professional get the authority to dictate value? Bourdieu answers this by re-embedding the museum professional in the broader system of the Artworld, insisting that, 'his ‘authority' itself… only exists in the relationship with the field of production as a whole.'[13] In other words, art acquires value from the whole smooth functioning of the Artworld.

Even though Google Art Project does not (yet?) include the collections of two of the most important museums of the western world TheLouvre, and The Vatican Museum, its accumulation of museum partners is impressive, and with few exceptions reinforces hierarchies that predate it. Contrary to much of the rhetoric about the Art Project, (contrary to rhetoric about global internet projects generally), the whole world does not share evenly in Google's efforts. The majority of the 230 institutions represented are in the countries of Europe and North America, probably because these countries already have the most developed museum sectors. Only one museum from the entire continent of Africa is represented (the Iziko National Gallery in South Africa.) This is not to condemn Google alone; choices about which museums to include are almost always made based on practicality, and rely on preexisting structures because these allow the project to develop much more quickly.[14] Regardless, in fundamental ways, Google Art Project is not a radical break from established museums.

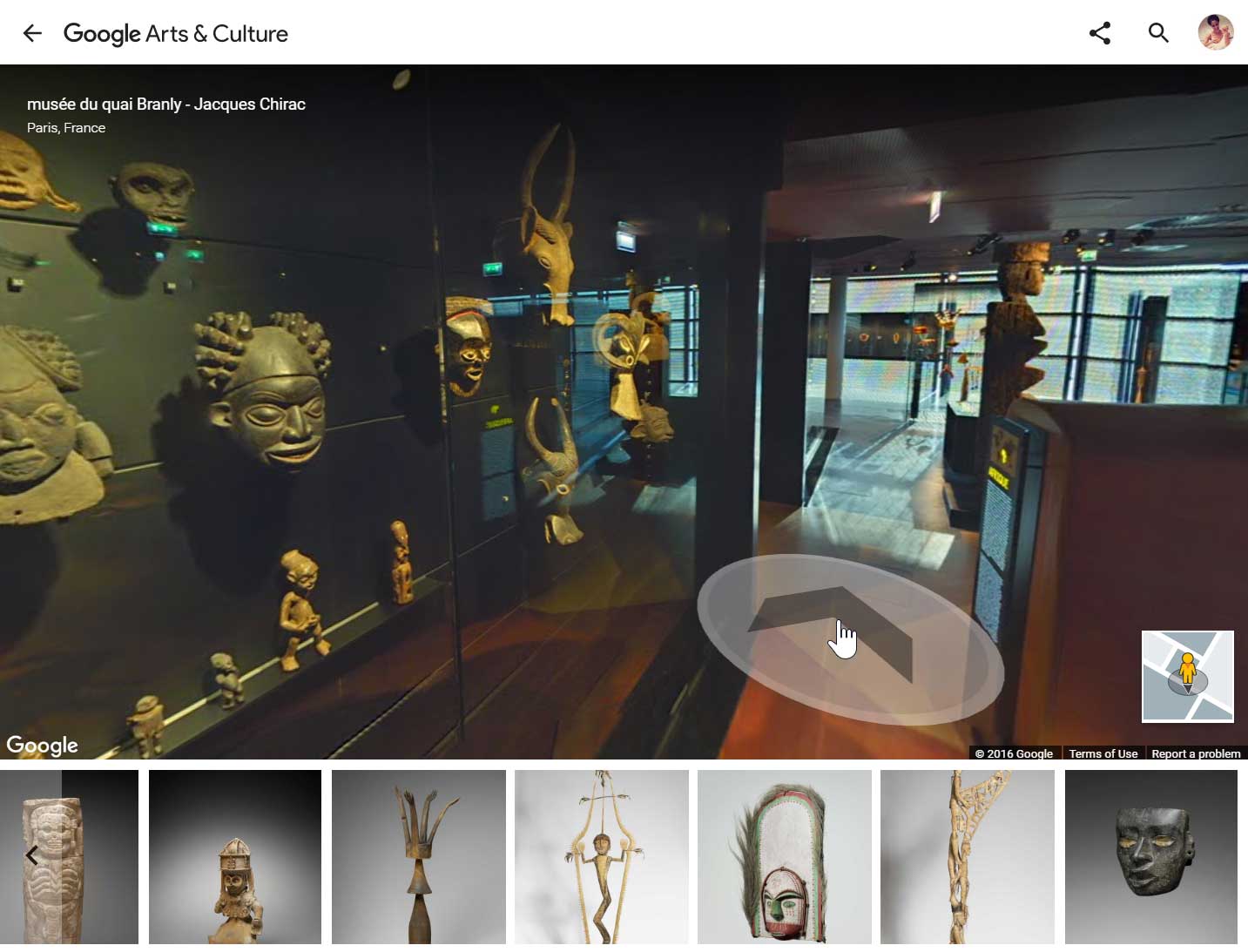

The overall structure of Google Art Project's interface is organized to both mimic and promote the museum. Each artwork you click on to examine links easily to the museum collection that artwork happens to come from. In fact, on the main screen for each art work, the other artworks from that particular museum collection that are digitized on Google Art Project run in a scrollable line across the bottom of the screen. In almost all cases, you can click to a 'street view' to bring you to a virtual tour of the museum space itself. Via this interface, you can scroll around the museum, see which works are hanging next to which other works, where benches for visitors have been placed; you can even move virtually through hallways into the next museum gallery. This is not the only way Google Art Project could have organized itself. It could have instead prioritized linkages between artworks and the original locations or eras they were produced, for example. In that case, the page for Cranach's Virgin and Child would be accompanied by a scrollable row of other works produced in 16th century Germany, rather than a row of other works that can be found at the Pushkin Museum. This is only one of the many, more or less logical ways Google Art Project could have, but did not, choose to organize the artworks in its collection. Choosing to organize the artworks around already established museum collections, as Google Art Project does, is not only practical, it also gives Google Art Project legitimacy. By complying with the general structure of the Artworld system, the Project is rewarded by gaining credibility as a relevant player.

Google Art Project is totally free for users and presents itself as a project for the public good. The Project is a subsidiary of Google Cultural Institute, whose mission is 'building tools to preserve and promote culture online.'[15] In other words, Google Art Project presents itself as an institution devoid of economic motivation. In truth, Google is one of the most successful companies in the world, built largely on the cultural capital of its reputation. In the long run, this cultural capital converts to economic gain. The Google Art Project feeds into the Google image in a way that is ultimately hugely monetarily valuable to the company, even as the role of money is obscured in their rhetoric.

When looked at through the lens of Bourdieu's symbolic capital, it is clear that Google Art Project does not so much make new meaning as piggy-back on the structure for meaning making already present in the Artworld. However, while this is by-and-large an accurate characterization, there are a number of other theoretical models we can use to try to understand the Google Art Project, and they lead us to slightly different insights.

Reproductions, Affordances and the Code of the 'Real'

James Gibson coined the term 'affordances' in 1977, and this concept has since then been an indispensable framework for thinking about the advantages and disadvantages involved in a particular technology. Gibson's defined affordances as: 'all action possibilities latent in the environment.'[16] When we borrow Gibson's concept to understand media technologies, such as Google Art Project, we can see that the website contains certain 'affordances;' in other words it supports certain actions but not others. In particular Google Art Project, like most digital media, affords the untrained visitor greater remixing and editing capabilities than its analog 'equivalent,' the museum. Iwork 2013 – productivity software suite. Visitors to Google Art Project can take advantage of this affordance when they create their own galleries and play at being curator. Furthermore, to return to my previously described example, the zoom function afforded me a clear look at the cracks covering the Cranach painting, and thus a more visceral sense of the nearly 500 years the painting has experienced since its creation. On the other hand, digitization 'looses' three-dimensional materiality of the artwork that is better perceived in a museum. Thinking in terms of affordances suggests that Google Art Project is, at least not completely, just aping museums in its functioning –it cannot. Because they are technologically different, the two media, museums and websites, have inherently different strengths and weaknesses.

Although she does not use the metaphor, affordances relates to the argument put forth by Kim Beil, in 'Seeing Syntax: Google Art Project and the Twenty-First-Century Period Eye,' one of the only academic articles as yet to theorize about the cultural implications of Google Art Project. Beil's main argument is that all reproductions are not created equal, and studying the qualities in a reproduction that we value in any particular historic moment can tell scholars a lot about the way our culture finds meaning in art. Reproductions, do not just iconically show their subject, like invisible windows, rather they also act as an index of the era and context in which they were made.[17] Beil explains that the high resolution, zoom-able, high contrast and interactive reproductions in Google Art project are not 'natural' or 'real' or 'better than the real thing,' as both the project creators, and users have described them. Their being described this way indicates however that we value the particular, specific qualities that they possess more fully than other reproductions. The affordances that Google Art Project technologies give are extreme brightness, high contrast, and sharpness. Beil says that 'critics describe these features, which allow us to examine reproduced artworks at an almost microscopic range and simulate the dimensionality of the object's surface, as part of Art Project's ‘reality effect,' but in actuality, these processes vary significantly from our real-life encounters with works of art.'[18] These images are not 'real' as much as they mimic our experience with other digital images, experiences we are trained to value through constant computer use. In other words, Google Art Project uses technologies particularly suited for promoting our contemporary code of the hyperreal. Articulated originally by cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard, the theory of the hyperreal recognizes that so often for society, the mediated world is more interesting than the real world.[19] We call it augmented, or enhanced reality. In our culture, certain things, certain reproductions, are coded as 'real,' or 'hyperreal.' The zoomable reproductions on Google Art Project are coded this way. It is just one code among thousands, but culturally, we privilege it. The fact that 'the real' is no less mediated than any other form, is what Beil is articulating in her thoughts about types of reproductions. The code has a history, and has meant different things throughout that history. Since the spread of photography in the mid-19th century, the code of 'the real' has been tied to a photographic-look, and the particular affordances of photography. Today, we are in a post-photograph age, and the code of 'the real' has shifted to emphasize those qualities that are better achieved by computer images. Beil's insights remind us that Google Art Project is not just opening up access to artworks for everyone around the world, as popular discourse seems to indicate, nor is it merely reinforcing the museum function, as a Bourdieu-ian analysis suggests, rather it is mediating and changing those artworks.

This insight takes us one step further than Bourdieu, because it acknowledges the fact that cultures, codes, and institutional functions do change. They change slowly, not by revolutions, but by baby-steps. New technologies do not cause these changes, so much as the particular affordances of a technology nudge our ways of seeing and interacting with culture into new directions. We see this in the example of the Cranach painting, and the way I can focus on the marks of time on its surface when I study it on the Google Art Project. This is but one of a number of examples of the small ways in which our interactions with Google Art Project are nudging us to notice new things about art.

Yuri Lotman, founder of the discipline 'cultural semiotics,' was interested in understanding how and why cultures change. He argued that the purpose of culture is to transmit memory, and the function of remixing, reframing and resignifying is to keep memory alive and relevant in each new era.[20] Google Art Projects remixes, reframes and resignifies older works of art and museum institutions. In doing this, it keeps them alive and relevant for our 21st century expectations.

The Future of Google Art Project

America Magazine reports that, thanks to Google Art Project, 'a child in some remote corner of the earth, who may never set foot in any art museum or have occasion to peruse an expensive art book, can examine masterpieces from around the world amassed over centuries.'[21] Another article states that Google Art Project 'is the ultimate application of the forum mindset: Not only do individuals get to interact directly with art, they also are able to manipulate it. Art is no longer something dissected only by snooty art historians we all find insufferable… it's a layman's conversation point.'[22] Both these quotes highlight the way Google Art Project is envisioned by its fans as revolutionary. In particular, these quotes seem to suggest that Google Art Project is democratizing the traditionally snobby, classist Artworld into something able to affect even the untrained and unprivileged every-day man and woman. Using Bourdieu's insights about symbolic capital, we can recognize that this great democratic revolution in art is an exaggeration; in fact Google Art Project largely maintains and even reinforces the Artworld structures. However, Google Art Project does have certain affordances give it the potential to be part of some sort of cultural change.

Google Art Project is still in its prototype stages. We cannot draw too many conclusions about its ultimate size and shape only by the content that is up on the site already, since Google is adding new things daily. We can only notice trends and follow them to logical hypotheses about the role Google Art Project may play for our culture in the coming years. There have been some hints in these trends that Google Art Project is indeed trying to make art more democratic.

Photographs and reproductions are what cultural theorist Roland Barthes termed floating signifiers; in other words, out of context, they can suggest any of hundreds of possible meanings to a viewer. Anchoring is the process that ties them to a particular meaning. For Barthes, anchoring often took place in the relationship between image and caption.[23] In Google Art Project, where captions play a subordinate role (you have to click on a further link in order to get a caption) anchoring occurs mostly in the way the Project contextualizes of these reproduction as high art, setting each reproduction in line with other objects of high art. By largely reinforcing Artworld hierarchies, Google Art Project has established its credibility as a consecrator of institutional capital; now it is in a position to make small changes, and consecrate works not normally seen as high art. There are a number of examples of less well known and less valued objects in the Google Art Project. By including some unusual collections among the more expected ones, using its institutional and technological capabilities to bestow value on these works, Google Art Project anchors these collections to the high art world. One example is the inclusion of the folk objects from the puppet theater collection in the small regional museum in eastern Germany, the Museum for Sachsen Folk Art. With or without its inclusion in Google Art Project, few people would deny that objects such as this toy chandelier show incredible craft and skill on the part of the maker. But because such objects are not part of the unified art history narrative do not fit well in the story of art's development toward modernism and beyond, they have rarely been conceived of as 'high art.' On Google Art Project, they are photographed with a clear, white-cube aesthetic and are zoom-able just like any of the other artworks. This contextualizes them, newly, as high art. Another, even more dramatic example is the inclusion of a collection called 'Sao Paolo Street Art.' This is not even a museum collection, but a collection of 189 images of graffiti from around the city of Sao Paolo, Brazil. There is very little textual information about this particular collection, either why Google Art Project chose to include it, or what makes street art in Sao Paolo particularly noteworthy. While not exactly revolutionary, both the puppet theater collection from Saxony, and the street art collection from Brazil are indications of the direction that Google Art Project is developing toward. Even though today the project is overwhelmingly dominated by a role call of greatest hits of art history, and partnerships with western museums of traditional high art, the small number of unexpected collections on the site is growing.

from the Puppet Theater Collection of the Museum for Saxen Folk Art

Bourdieu has noted that pop art, and other art movements that seemed to gain their raison d'etre from trying to break the illusions are what Bourdieu calls 'ritual sacrilege' and are always swallowed to become part of the system. Critiques or mockeries of the artworld 'are immediately converted into artistic ‘acts,' recorded as such, and thus consecrated and celebrated by the makers of taste.'[24] But maybe we should not discount these artist interventions as meaningless. Since April 2012, the Art Gallery of Ontario has been a partner with Google Art Project. While their collection includes much that fits with the traditional oil-on-canvas-type artworks most common in Google Art Project, the collection also includes the very interesting, contemporary ouvre by artist Jon Rafman titled Brand New Paint Job. Putnam's work is one of the first artist responses to Google Art Project. He uses images accessible on Google Art Project and appropriates them to create intricate virtual settings. As one anonymous user has written in his/her gallery on Google Art Project, 'Rafman's series, Brand New Paint Job, the collection of artworks at the center of the exhibition, straddle the line between artistic sacrilege and homage.'[25] As James Putnam points out in his book Art/Artifact, the Artworld functions not just in the direction of museums conferring value on artworks, but throughout history, 'artists exert an equally powerful influence on museums.'[26] His book traces the history of artistic interventions into museum display practices. Important interventions have sparked dialogue, and arguably changed the Artworld. Rafman's 'intervention' is the first of what we can only expect will be many art projects inspired be and reacting to the particular structure and meaning of Google Art Project. It suggests the potential for Google Art Project to be a resource for artists and a spark for dialog.

Rafman Brand New Paint Job ECarr Masterbedroom

Back in the 1950s, André Malraux envisioned a 'Musée Imaginaire,' a world of art accessible to people far more easily and cheaply than ever before. With improvements in photographic technology, Malraux saw this imaginary museum as an imminent possibility. In photographic reproductions of artworks, we loose a sense of scale, context, three-dimensionality and geographic specificity. Malraux recognized how all these losses are also a gain: by compressing them all into a single format, photographs equalize the value of artworks.[27] Malraux was an idealist. The artworld has remained largely elitist and driven by symbolic capital in the decades since he wrote, despite photographic technology. Digital technology and the Google Art Project will not create a revolution either. Nonetheless, they are part of a larger, slower trend toward a broader, more democratic and contestable definition of art.

[2] 'Aura' as it relates to art, is a term that has been notoriously vague and overused since Walter Benjamin made it popular by stating that technological reproduction of a work of art –he was speaking specifically of photography and film in the 1930s, distances us from an artworks 'aura,' decontextualizing it, and removing from the ritual context it was always associated with in previous centuries.

[4]ibid 45

[6] Irvine 'The Museum System'

[8]ibid 243

[10]ibid 248

[12] Bourdieu 'The Production of Belief' 262

[14] An important preexisting structure that Google Art Project cannot directly break with is copyright law. The majority of the works on the Project come from before the 1920s because these run into fewer copyright entanglements. Also, Google Art Project gets around the complications of liability by requiring museum partners to take all responsibility for remaining within copyright rules.

[16] Wikipedia article on James Gibson

[18] Beil 25-26

[20] Lotman 214

[22] Burgin

[24] Bourdieu 'The Production of Belief' 266

[25] http://www.googleartproject.com/galleries/26765288/33346242/details/

Google Art Project is totally free for users and presents itself as a project for the public good. The Project is a subsidiary of Google Cultural Institute, whose mission is 'building tools to preserve and promote culture online.'[15] In other words, Google Art Project presents itself as an institution devoid of economic motivation. In truth, Google is one of the most successful companies in the world, built largely on the cultural capital of its reputation. In the long run, this cultural capital converts to economic gain. The Google Art Project feeds into the Google image in a way that is ultimately hugely monetarily valuable to the company, even as the role of money is obscured in their rhetoric.

When looked at through the lens of Bourdieu's symbolic capital, it is clear that Google Art Project does not so much make new meaning as piggy-back on the structure for meaning making already present in the Artworld. However, while this is by-and-large an accurate characterization, there are a number of other theoretical models we can use to try to understand the Google Art Project, and they lead us to slightly different insights.

Reproductions, Affordances and the Code of the 'Real'

James Gibson coined the term 'affordances' in 1977, and this concept has since then been an indispensable framework for thinking about the advantages and disadvantages involved in a particular technology. Gibson's defined affordances as: 'all action possibilities latent in the environment.'[16] When we borrow Gibson's concept to understand media technologies, such as Google Art Project, we can see that the website contains certain 'affordances;' in other words it supports certain actions but not others. In particular Google Art Project, like most digital media, affords the untrained visitor greater remixing and editing capabilities than its analog 'equivalent,' the museum. Iwork 2013 – productivity software suite. Visitors to Google Art Project can take advantage of this affordance when they create their own galleries and play at being curator. Furthermore, to return to my previously described example, the zoom function afforded me a clear look at the cracks covering the Cranach painting, and thus a more visceral sense of the nearly 500 years the painting has experienced since its creation. On the other hand, digitization 'looses' three-dimensional materiality of the artwork that is better perceived in a museum. Thinking in terms of affordances suggests that Google Art Project is, at least not completely, just aping museums in its functioning –it cannot. Because they are technologically different, the two media, museums and websites, have inherently different strengths and weaknesses.

Although she does not use the metaphor, affordances relates to the argument put forth by Kim Beil, in 'Seeing Syntax: Google Art Project and the Twenty-First-Century Period Eye,' one of the only academic articles as yet to theorize about the cultural implications of Google Art Project. Beil's main argument is that all reproductions are not created equal, and studying the qualities in a reproduction that we value in any particular historic moment can tell scholars a lot about the way our culture finds meaning in art. Reproductions, do not just iconically show their subject, like invisible windows, rather they also act as an index of the era and context in which they were made.[17] Beil explains that the high resolution, zoom-able, high contrast and interactive reproductions in Google Art project are not 'natural' or 'real' or 'better than the real thing,' as both the project creators, and users have described them. Their being described this way indicates however that we value the particular, specific qualities that they possess more fully than other reproductions. The affordances that Google Art Project technologies give are extreme brightness, high contrast, and sharpness. Beil says that 'critics describe these features, which allow us to examine reproduced artworks at an almost microscopic range and simulate the dimensionality of the object's surface, as part of Art Project's ‘reality effect,' but in actuality, these processes vary significantly from our real-life encounters with works of art.'[18] These images are not 'real' as much as they mimic our experience with other digital images, experiences we are trained to value through constant computer use. In other words, Google Art Project uses technologies particularly suited for promoting our contemporary code of the hyperreal. Articulated originally by cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard, the theory of the hyperreal recognizes that so often for society, the mediated world is more interesting than the real world.[19] We call it augmented, or enhanced reality. In our culture, certain things, certain reproductions, are coded as 'real,' or 'hyperreal.' The zoomable reproductions on Google Art Project are coded this way. It is just one code among thousands, but culturally, we privilege it. The fact that 'the real' is no less mediated than any other form, is what Beil is articulating in her thoughts about types of reproductions. The code has a history, and has meant different things throughout that history. Since the spread of photography in the mid-19th century, the code of 'the real' has been tied to a photographic-look, and the particular affordances of photography. Today, we are in a post-photograph age, and the code of 'the real' has shifted to emphasize those qualities that are better achieved by computer images. Beil's insights remind us that Google Art Project is not just opening up access to artworks for everyone around the world, as popular discourse seems to indicate, nor is it merely reinforcing the museum function, as a Bourdieu-ian analysis suggests, rather it is mediating and changing those artworks.

This insight takes us one step further than Bourdieu, because it acknowledges the fact that cultures, codes, and institutional functions do change. They change slowly, not by revolutions, but by baby-steps. New technologies do not cause these changes, so much as the particular affordances of a technology nudge our ways of seeing and interacting with culture into new directions. We see this in the example of the Cranach painting, and the way I can focus on the marks of time on its surface when I study it on the Google Art Project. This is but one of a number of examples of the small ways in which our interactions with Google Art Project are nudging us to notice new things about art.

Yuri Lotman, founder of the discipline 'cultural semiotics,' was interested in understanding how and why cultures change. He argued that the purpose of culture is to transmit memory, and the function of remixing, reframing and resignifying is to keep memory alive and relevant in each new era.[20] Google Art Projects remixes, reframes and resignifies older works of art and museum institutions. In doing this, it keeps them alive and relevant for our 21st century expectations.

The Future of Google Art Project

America Magazine reports that, thanks to Google Art Project, 'a child in some remote corner of the earth, who may never set foot in any art museum or have occasion to peruse an expensive art book, can examine masterpieces from around the world amassed over centuries.'[21] Another article states that Google Art Project 'is the ultimate application of the forum mindset: Not only do individuals get to interact directly with art, they also are able to manipulate it. Art is no longer something dissected only by snooty art historians we all find insufferable… it's a layman's conversation point.'[22] Both these quotes highlight the way Google Art Project is envisioned by its fans as revolutionary. In particular, these quotes seem to suggest that Google Art Project is democratizing the traditionally snobby, classist Artworld into something able to affect even the untrained and unprivileged every-day man and woman. Using Bourdieu's insights about symbolic capital, we can recognize that this great democratic revolution in art is an exaggeration; in fact Google Art Project largely maintains and even reinforces the Artworld structures. However, Google Art Project does have certain affordances give it the potential to be part of some sort of cultural change.

Google Art Project is still in its prototype stages. We cannot draw too many conclusions about its ultimate size and shape only by the content that is up on the site already, since Google is adding new things daily. We can only notice trends and follow them to logical hypotheses about the role Google Art Project may play for our culture in the coming years. There have been some hints in these trends that Google Art Project is indeed trying to make art more democratic.

Photographs and reproductions are what cultural theorist Roland Barthes termed floating signifiers; in other words, out of context, they can suggest any of hundreds of possible meanings to a viewer. Anchoring is the process that ties them to a particular meaning. For Barthes, anchoring often took place in the relationship between image and caption.[23] In Google Art Project, where captions play a subordinate role (you have to click on a further link in order to get a caption) anchoring occurs mostly in the way the Project contextualizes of these reproduction as high art, setting each reproduction in line with other objects of high art. By largely reinforcing Artworld hierarchies, Google Art Project has established its credibility as a consecrator of institutional capital; now it is in a position to make small changes, and consecrate works not normally seen as high art. There are a number of examples of less well known and less valued objects in the Google Art Project. By including some unusual collections among the more expected ones, using its institutional and technological capabilities to bestow value on these works, Google Art Project anchors these collections to the high art world. One example is the inclusion of the folk objects from the puppet theater collection in the small regional museum in eastern Germany, the Museum for Sachsen Folk Art. With or without its inclusion in Google Art Project, few people would deny that objects such as this toy chandelier show incredible craft and skill on the part of the maker. But because such objects are not part of the unified art history narrative do not fit well in the story of art's development toward modernism and beyond, they have rarely been conceived of as 'high art.' On Google Art Project, they are photographed with a clear, white-cube aesthetic and are zoom-able just like any of the other artworks. This contextualizes them, newly, as high art. Another, even more dramatic example is the inclusion of a collection called 'Sao Paolo Street Art.' This is not even a museum collection, but a collection of 189 images of graffiti from around the city of Sao Paolo, Brazil. There is very little textual information about this particular collection, either why Google Art Project chose to include it, or what makes street art in Sao Paolo particularly noteworthy. While not exactly revolutionary, both the puppet theater collection from Saxony, and the street art collection from Brazil are indications of the direction that Google Art Project is developing toward. Even though today the project is overwhelmingly dominated by a role call of greatest hits of art history, and partnerships with western museums of traditional high art, the small number of unexpected collections on the site is growing.

from the Puppet Theater Collection of the Museum for Saxen Folk Art

Bourdieu has noted that pop art, and other art movements that seemed to gain their raison d'etre from trying to break the illusions are what Bourdieu calls 'ritual sacrilege' and are always swallowed to become part of the system. Critiques or mockeries of the artworld 'are immediately converted into artistic ‘acts,' recorded as such, and thus consecrated and celebrated by the makers of taste.'[24] But maybe we should not discount these artist interventions as meaningless. Since April 2012, the Art Gallery of Ontario has been a partner with Google Art Project. While their collection includes much that fits with the traditional oil-on-canvas-type artworks most common in Google Art Project, the collection also includes the very interesting, contemporary ouvre by artist Jon Rafman titled Brand New Paint Job. Putnam's work is one of the first artist responses to Google Art Project. He uses images accessible on Google Art Project and appropriates them to create intricate virtual settings. As one anonymous user has written in his/her gallery on Google Art Project, 'Rafman's series, Brand New Paint Job, the collection of artworks at the center of the exhibition, straddle the line between artistic sacrilege and homage.'[25] As James Putnam points out in his book Art/Artifact, the Artworld functions not just in the direction of museums conferring value on artworks, but throughout history, 'artists exert an equally powerful influence on museums.'[26] His book traces the history of artistic interventions into museum display practices. Important interventions have sparked dialogue, and arguably changed the Artworld. Rafman's 'intervention' is the first of what we can only expect will be many art projects inspired be and reacting to the particular structure and meaning of Google Art Project. It suggests the potential for Google Art Project to be a resource for artists and a spark for dialog.

Rafman Brand New Paint Job ECarr Masterbedroom

Back in the 1950s, André Malraux envisioned a 'Musée Imaginaire,' a world of art accessible to people far more easily and cheaply than ever before. With improvements in photographic technology, Malraux saw this imaginary museum as an imminent possibility. In photographic reproductions of artworks, we loose a sense of scale, context, three-dimensionality and geographic specificity. Malraux recognized how all these losses are also a gain: by compressing them all into a single format, photographs equalize the value of artworks.[27] Malraux was an idealist. The artworld has remained largely elitist and driven by symbolic capital in the decades since he wrote, despite photographic technology. Digital technology and the Google Art Project will not create a revolution either. Nonetheless, they are part of a larger, slower trend toward a broader, more democratic and contestable definition of art.

[2] 'Aura' as it relates to art, is a term that has been notoriously vague and overused since Walter Benjamin made it popular by stating that technological reproduction of a work of art –he was speaking specifically of photography and film in the 1930s, distances us from an artworks 'aura,' decontextualizing it, and removing from the ritual context it was always associated with in previous centuries.

[4]ibid 45

[6] Irvine 'The Museum System'

[8]ibid 243

[10]ibid 248

[12] Bourdieu 'The Production of Belief' 262

[14] An important preexisting structure that Google Art Project cannot directly break with is copyright law. The majority of the works on the Project come from before the 1920s because these run into fewer copyright entanglements. Also, Google Art Project gets around the complications of liability by requiring museum partners to take all responsibility for remaining within copyright rules.

[16] Wikipedia article on James Gibson

[18] Beil 25-26

[20] Lotman 214

[22] Burgin

[24] Bourdieu 'The Production of Belief' 266

[25] http://www.googleartproject.com/galleries/26765288/33346242/details/

[27] Malraux 9-12

Works Cited:

America Press 'Googling a Masterpiece' 2012.

Barthes, Roland Mythologies, trans. Annette Lavers New York: The Noonday Press 1957.

Baudrillard, Jean Simulacra and Simulation trans. Sheila Faria Glaser. Michigan Press 1981.

Beil, Kim 'Seeing Syntax: Google Art Project and the Twenty-First Century Period Eye,' Afterimage 40:4 (Jan/Feb 2013), 22-27

Benjamin, Walter 'Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit'

Bolter, Jay David and Richard Grusin Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2000.

Google Arts And Culture Website

Bourdieu, Pierre Forms of Capital trans. Richard Nice. Göttigen: Otto Schartz & Co. 1983.

Bourdieu, Pierre and Richard Nice 'The Production of Belief: Contribution to an economy of symbolic goods' Media, Culture and Society 2 (1980), 261-293.

Burgin, Leah 'Goggling over Google's Art Project' The Michigan Daily February 6, 2011.

Danto, Arthur 'The Art World' The Journal of Philosophy 61:19 (1964) 571-584.

Gittelman, Lisa Always Already New: History and the Data of Culture. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2008.

Irvine, Martin: 'The Museum System: Themes, Questions and Issues for Art Museums Today' http://www9.georgetown.edu/faculty/irvinem/visualarts/museums/MuseumModule.html

Lotman, Yuri 'On the Semiotic Mechanism of Culture' New Literary History 9:2 (Winter 1978) 211-232.

Art Google Programs

Putnam, James Art and Artifact: The Museum as Medium New York: Thames and Hudson, 2001.

Google Art Project Prado Museum

Malraux, André Museum Without Walls trans. Stuart Gilbert and Francis Price. New York: Doubleday and Company Inc. 1967.